“…sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

– The White Queen, Through the Looking Glass

Should an asset owner rely on historical performance data to select managers? The efficacy of doing so depends on the answers to three questions:

- What fraction of the manager universe is truly gifted?

- How gifted are they?

- How lucky might the “ordinary” managers be?

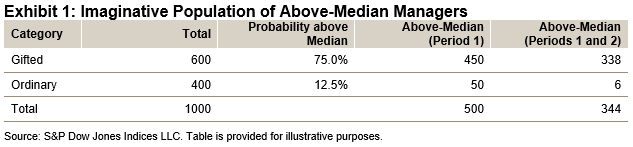

For example: Suppose we assume that 60% of all managers are “gifted” and 40% are “ordinary,” that a gifted manager has a 75% probability of achieving above-median results, and that an ordinary manager has a 12.5% chance of doing the same. Exhibit 1 shows some implications of these assumptions for a 1000-manager universe.

Exhibit 1 contains both good and bad news for our hypothetical asset owner. The good news is that after one period, 90% (450/500) of the above-median managers are genuinely gifted; if our assumptions are correct, hiring only from the above-median pool will lift the odds of success. The bad news is that our assumptions are almost certainly incorrect, not to say wildly unrealistic. Why? Because these assumptions imply that 69% (344/500) of period 1’s above-median managers will also be above median in period 2—a persistence rate far greater than those we actually observe. Exhibit 1 is, sadly, an artifact of wishful thinking.

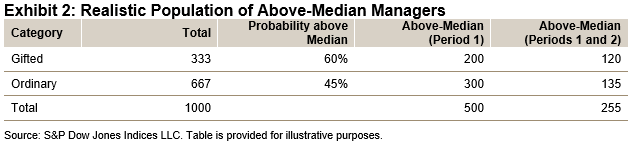

If Exhibit 1’s assumptions are clearly wrong, what alternatives might be more realistic? To be more modest, we can reduce the population of gifted managers from 60% to one-third, reduce their probability of ranking above median from 75% to 60%, and narrow the gap between the gifted and the ordinary by setting the ordinary managers’ chance of being above median at 45%. As before, Exhibit 2 contains both good and bad news for our hypothetical asset owner.

The good news is that using Exhibit 2’s assumptions, 51% (255/500) of period 1’s above-median managers should repeat that performance in period 2. Although we don’t often see results that good, 51% persistence is not unheard of, and so Exhibit 2 is at least a somewhat plausible model of reality.

The bad news in Exhibit 2 is that only 40% (200/500) of period 1’s above-median managers are genuinely gifted; 60% of them got there through luck rather than skill. And perhaps worse news: only 47% (120/255) of the managers who are above median in two consecutive periods are genuinely gifted. In other words, an asset owner who hires from the above-median pool is more likely to get an ordinary manager than a gifted one. Even if we assume that genuinely gifted managers exist—and that they stay gifted over time—hiring an above-median performer provides a less-than-even chance of finding the gifted manager we are seeking.

Active management is difficult, as readers of our SPIVA Scorecards know well; identifying outstanding managers is perhaps equally challenging. Relying on historical performance rankings is unlikely to be helpful.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.