In January 2020, S&P Dow Jones Indices released a paper for the S&P Eurozone Paris-Aligned Climate Index Concept (PAC Concept). The PAC Concept aims to align with the proposals of the EU Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (TEG), as published in its Final Report on Climate Benchmarks and Benchmarks’ ESG Disclosure dated September 2019,1 for the Paris-Aligned Benchmark—the more stringent of the two benchmarks proposed by the EU. Furthermore, the PAC Concept aims to align with the TCFD’s recommendations on Climate Related Financial Risks and Opportunities. Since publication of the paper, we have received a lot of feedback on our approach, particularly with respect to the application of high climate impact sector neutrality.2

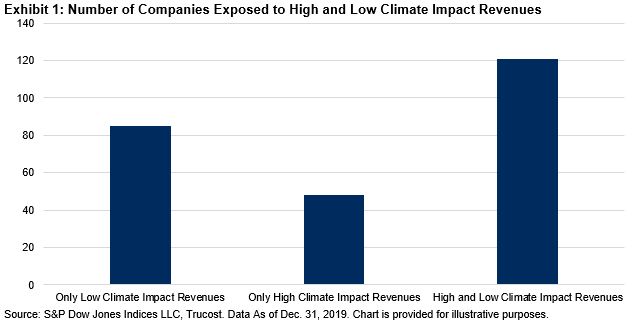

The PAC Concept uses “Trucost3 sector” data, which has been mapped to the NACE4 sections defined as high emitting.5 There are 464 “Trucost sectors,” which are based on revenue streams. Therefore, companies can have exposure to multiple different “Trucost sectors” and by extension, exposure to both high and low climate impact sectors. This can be seen in Exhibit 1, where more companies have a mix of high and low climate impact revenue streams than those with only low impact or only high impact.

The PAC Concept’s granular view on revenues from high climate impact sectors ensures the same revenues, per dollar invested, as the underlying index. This objective would not be achievable if we only used company-level sector classification. This helps to minimize any unintentional greenwashing from index design within the TEG proposed high climate impact sector framework when company classifications are applied, rather than revenue classifications. Constructing the index using sector classifications means index design can transfer weight into companies with far less exposure to high-climate-impact sectors, as opposed to companies with more carbon-efficient practices. The latter are likely to be at the forefront of the low-carbon transition.

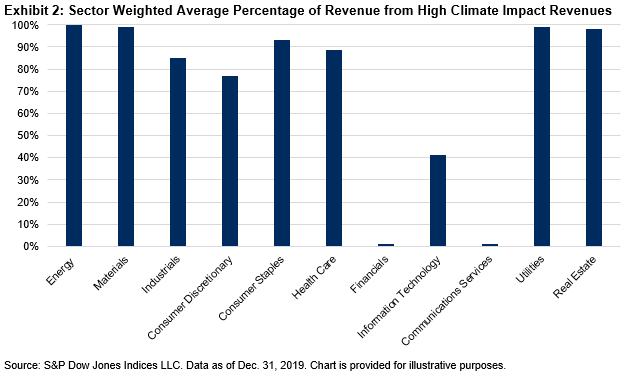

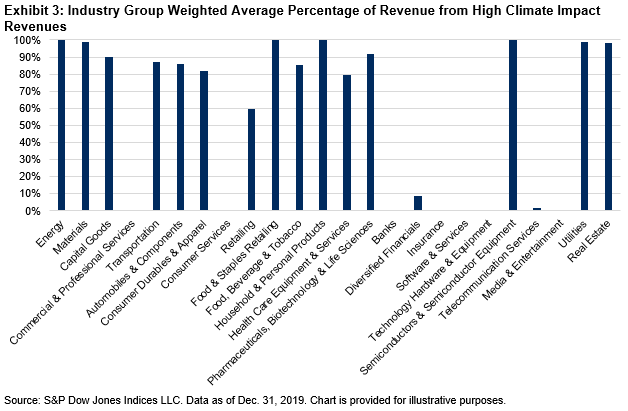

There are revenues from both high and low climate impact sectors6 in most GICS® sectors (see Exhibit 2). The same is observed within GICS industry groups (see Exhibit 3).

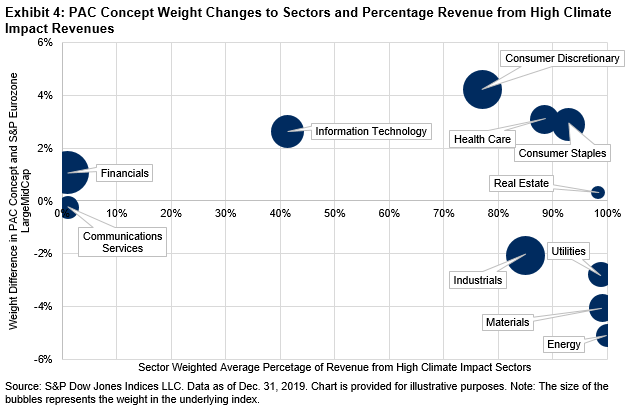

Exhibit 4 shows where large weights from Energy and Materials may have been placed within high climate impact revenue streams. The X axis shows the percentage of revenues coming from high climate impact sectors and the Y axis shows the difference in sector weight between the parent index and PAC Concept. The size of the bubbles represents the weight of each sector within the parent index.

We can see weight being taken from Energy and Materials. A lot of this weight appears to be redistributed into Consumer Staples and Health Care. These two sectors had slightly less exposure to high climate impact sectors; however, this was where much of the weight ended up. There was also an overweight of the Consumer Discretionary sector, which has high climate impact exposure.

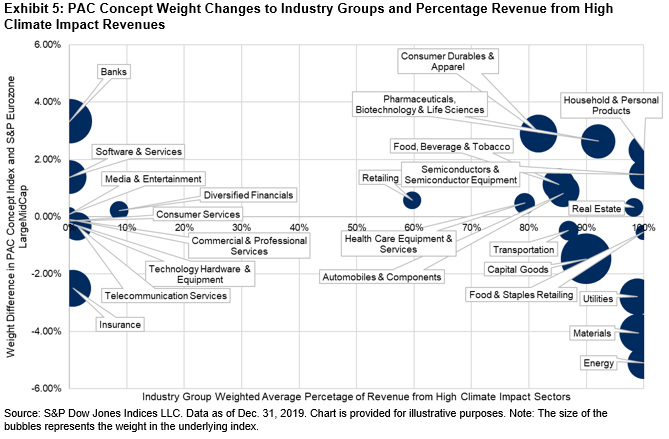

GICS industry group analysis shows a similar story at the more granular level. Household & Personal Products, Pharmaceuticals, Biotechnology & Life Sciences, and Semiconductors & Semiconductor Equipment all saw overweighting, while having high exposure to high climate impact sectors.

1 The EU Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance Final Report on Climate Benchmarks and Benchmarks’ ESG Disclosure, September 2019. The final report will serve as the basis for the European Commission for the drafting of the delegated acts under Regulation 2019/2089.

2 Climate Impact Sector neutrality is mandated by TEG in its Final Report.

3 A part of S&P Global.

4 NACE (a French term “nomenclature statistique des activités économiques dans la Communauté européenne”) is a revenue-based sector classification used within the European Union.

5 High climate impact sectors as defined by the TEG in the Final Report.

6 The percentage of revenues has been calculated as the weighted average of the percentage of each company’s revenues from high climate impact sectors, weighted by their weight in the S&P Eurozone LargeMidCap.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.