Preferred stocks are a class of capital stock that pays dividends at a specified rate and has a preference over common stock in the payment of dividends and the liquidation of assets.

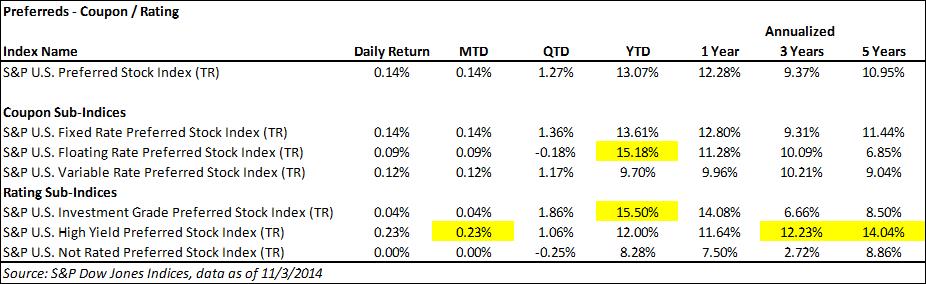

The S&P U.S. Preferred Stock Index is designed to serve the investment community’s need for an investable benchmark representing the U.S. preferred stock market. The Index has currently returned a total return of 0.14% month-to-date and 13.07% year-to-date.

A 13% return in the current low rate environment is fantastic but if you delve a little deeper you can do even better. S&P Dow Jones Indices has developed sub-indices that break-out the preferred parent index into coupon type and rating sub-indices.

Of the coupon types, the S&P U.S. Floating Rate Preferred Stock Index is outperforming the parent index with a 15.18% year-to-date. The reason floaters have not pushed the parents return up higher is that floaters only constitute 4% of the overall index.

Rating sub-indices are equally impressive as the S&P U.S. High Yield Preferred Stock Index has returned 0.23% for the month, while the S&P U.S. Investment Grade Preferred Stock Index year-to-date has returned 15.5%. Depending on your risk tolerance, both rating segments have provided consistent returns though the high yield sub-index has performed better over 3 and 5 year time horizons.